Why I Love the Journals in Myst So Much

Oct 22, 2024

I first played Myst as a child. Before I could play the game myself, I watched my dad play. Or maybe I’m misremembering and I never graduated to playing it on my own. Maybe sometimes I played, but mostly my dad played and I watched, because the puzzles were too difficult for me to solve without help. This seems likely because I can remember the sights and sounds of Myst but have no memory of feeling stumped or frustrated.

Thanks, Dad.

I recently played Myst again. The island of Myst is of course a make-believe, virtual space that exists as ones and zeroes in the computer. It is also a very real place in which I passed part of my childhood, real in the sense that returning to it now evokes real feelings that I have felt at other times only when revisiting a childhood bedroom or returning to a neighborhood I haven’t lived in for years. Why hello again, my favorite old stuffed animal! My heart thrums in recognition. Hello again, elevator in the secret tower behind the bookshelf on the island of Myst! I remember exactly the whir and racket you made.

I’ve enjoyed going back to Myst because it’s been interesting to see what is still as I remember it and what surprises me. There is a dream-like, fantastic quality to the world of Myst that lodged it in my brain as a child. I was not disappointed to discover that unique quality still there; Myst is still unlike other games, even after all these years. On the other hand, some of the puzzles in Myst are less fun and more arbitrary than I remember. There are many other games out there today with puzzles that are better justified by the world they exist in. Some of the puzzles in Myst seem like random impediments to the player’s progress that only exist because somewhat thought they would be a cool puzzle.

But what struck me most of all as I replayed Myst was how much I enjoyed reading Atrus’ journals.

Atrus is one of the main characters in the game. He keeps a library in the center of the island of Myst. When you discover it, most of his books have been destroyed in a fire, but a few survive that you can read. These books, his journals, recount his travels to four different “ages,” each of which is a little terrarium universe that Atrus is somehow able to travel to via special “linking” books. Atrus creates these linking books; whether he conjures the ages into being by creating the linking books or merely opens portals to them is unclear.

A page from Atrus’ journal about the Stoneship Age.

The journals are a cross between a ship’s log and a scientist’s lab notebook. In genteel cursive, Atrus writes about uncovering cave systems, harnessing geothermal energy, and cataloging constellations. Where an age is populated, he also plays the anthropologist, writing about the culture and customs of the people he has met there. The journals include sketches of vistas, architecture, and machinery.

I love these journals. There is something about them that I think captures the essence of Myst, or at least the essence of my affection for the Myst games. I love them so much that I did some googling to see if I could order a printed copy of any of the journals featured in the game. Sadly, you cannot, but in the course of my googling I discovered that someone made their own Myst journal chronicling their journey through a later game in the Myst series. I also discovered that someone wrote Myst fan fiction in the style of a Myst journal, recounting the events of the original game from the perspective of the player character. So it appears I’m far from the only one with a deep love for these journals.

The sequels to Myst also feature journals, written by different characters but in a similar style to the original ones written by Atrus. So someone responsible for developing the games seems to have agreed with me that they are part of the DNA of the franchise.

Why are the journals so important? Why do I find them so captivating? Many gamers might find the part of a video game where you are literally asked to read a book tedious, but the Myst journals have a deep appeal to me and other Myst fans. How can I account for that difference?

I think the answer comes down to why people play video games. As I was thinking about the Myst journals, I remembered watching a YouTube video about how people’s personality influences the games they play. The video describes research conducted by a market research firm called Quantic Foundry that suggests people might play games to reinforce their own identity.

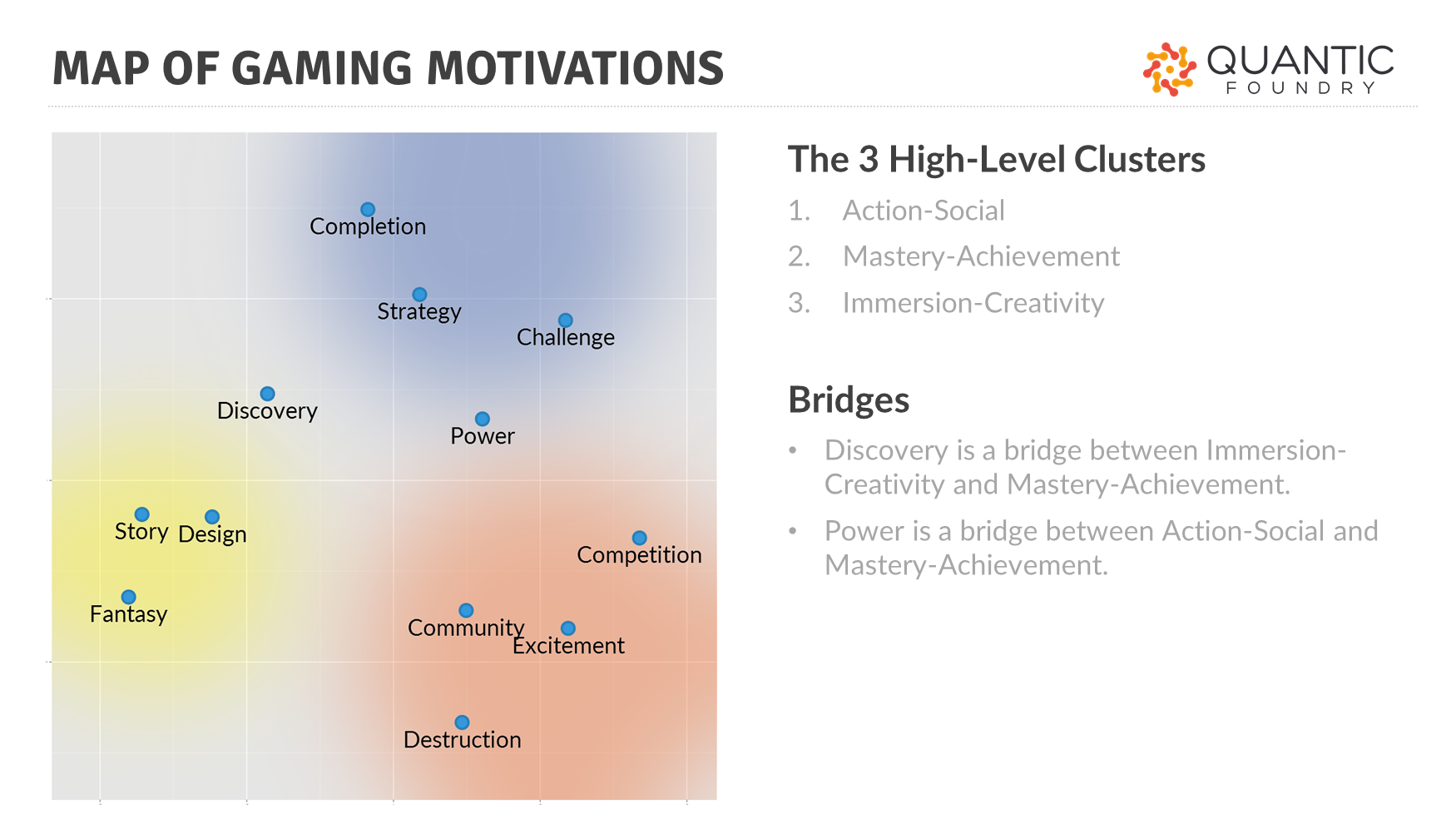

Quantic Foundry is led by a man named Nick Yee. In a blog post, Yee writes about how gamers’ motivations for playing can be clustered into three categories. Yee found, based on data collected from thousands of people, that one cluster of gamers looks for high-action, socially involved experiences; another cluster looks for games about narrative, exploration, and creative expression; while a third cluster looks for games that involve strategy and challenge. He calls these clusters the “Action-Social” cluster, the “Immersion-Creativity” cluster, and the “Mastery-Achievement” cluster.

Call of Duty would be a classic “Action-Social” game. Minecraft would appeal to the “Immersion-Creativity” cluster. A strategy game like Starcraft would appeal to the “Mastery-Achievement” cluster.

Quantic Foundry’s clustering of common gaming motivations.

In a follow-up blog post, Yee writes about how these three clusters correlate with different personality traits. By asking gamers to complete a Big Five personality assessment in addition to providing data about their gaming motivations, Yee determined that the “Action-Social” cluster tended to contain people scoring high in extroversion, the “Immersion-Creativity” cluster tended to contain people scoring high in openness, and the “Mastery-Achievement” cluster tended to contain people scoring high in conscientiousness.

I don’t know enough about how to conduct psychology research to judge the validity of these findings. That said, I love the way Yee summarizes his results:

Games are often stereotyped as escapist fantasies—where people get to pretend to be something they’re not. But what the data shows is that gamers play games that align with their personalities. In the same way that people select the news and media that reinforce their worldviews, gamers select the games that reinforce their identities. For example, gamers who are extroverted prefer more social and action-oriented games. Gamers who are more conscientious prefer games with long-term thinking and planning.

The games we play are a reflection, not an escape, from our own identities. In this sense, people play games not to pretend to be someone they’re not, but to become more of who they really are.

This resonates with me because I realize it’s true about my own attachment to video games.

I love to learn. I was a good student in school, and perhaps because I received so much positive feedback and praise for being a good student I now see myself as a “learner.” Without question, the motivation from Yee’s taxonomy of gaming motivations that fits me best is the “discovery” motivation. My favorite thing about video games is that each game is a little universe full of new places to explore and systems to understand. Playing video games, for me, is recreational learning. As I play a game and learn my way around its virtual environments and the rules of its systems, I get to feel clever. I get to feel like I’m acing the exam. In the games I enjoy most, I get to be a curious, perceptive person and have those personality traits rewarded by progress and success.

I will sometimes play a Call of Duty and enjoy it. I also like strategy games. But often what I enjoy most about these games is discovering new routes in a level or new tactics that help me perform well. The competitive element is not that important to me.

And there are games that I’ve enjoyed like Dear Esther or Gone Home, which arguably aren’t games at all, because they have no formal rules or ways to “win.” They are just virtual spaces to explore. But that’s my jam!

So it should be no surprise that I like Myst. Rand Miller, one of the creators of Myst, says in an interview that he and his brother, Robyn, started their company “for the purpose of making worlds. We just wanted to make places, not games.” That makes so much sense to me, because I suspect part of what made Myst such a success—and also a great game for “discovery” gamers—is that it is so believable and self-consistent. It feels like a place that exists separately from you, the player, with an internal logic that you must discover and work within. That distinguishes it from many other games that feel like artificial challenge arenas made just for the player.

As for the Myst journals, I suspect what makes them so appealing to fans of the Myst games is that they are a distillation of the discovery mindset that draws us to the games in the first place.

Atrus’ journals show off his powers of observation and his inquisitiveness. He writes about all the various things he notices in the ages he visits, even curiosities that have no immediate application toward his goals. You can read these journals before you visit the ages he is describing. The journals are like a guide for how to play Myst, a model of the attitude you ought to have to make progress in the game. It’s natural that people would want to create a Myst-like journal recording their own experience navigating Myst, or that people would write fan fiction about the player character in the style of a journal, because the game is already priming players to encounter its ages the same way Atrus does, like a particularly thoughtful scientist or explorer, jotting down notes and sketches along the way. Atrus is the ultimate “discovery” gamer.

There have been other games released in recent years, like Return of the Obra Dinn or The Outer Wilds, that follow in the legacy of Myst by being primarily about discovery and exploration in a believable world. These games also feature journals, so there seems to be something about a journal that meshes well with this genre of game. In Return of the Obra Dinn and The Outer Wilds, things go one step further than in Myst; the journals in those games are journals of the player’s experience that automatically get filled in with information as the player makes discoveries in the game world. What is merely suggested in Myst by Atrus’ journals—that you, like Atrus, are in an alien environment where you will have be curious and carefully record your every observation to make sense of things—is turned into a core feature of the experience, something done for you by the game. You don’t have to go to the trouble of pulling out pen and paper, but you still get to feel like you are keeping a journal of your findings.

Though I love these newer games, the journals in Myst will always be special to me. They epitomize the identity I’m often seeking to reinforce when I play video games. The journals make me realize that I enjoy Myst because I enjoy role-playing as Atrus, a figure out of a Jules Verne novel with a large library and a literary vocation who gets by using his powers of observation and his quill. The journals capture something about the qualities—curiosity, intelligence, erudition—that I seek to cultivate in myself and admire in others. The journals teach me something about who I want to be.