Snapshots or Patches? Does It Matter?

Aug 18, 2025

Although overwhelmingly people use Git, other version control systems exist. Some are even new and shiny and experimenting with features that Git doesn’t have.

I recently worked my way through this excellent tutorial for Jujutsu. It excited me, because it made me realize that the design space for version control systems is much larger and more unexplored than I had imagined.

But I don’t want to talk about Jujutsu. The docs for Jujutsu mention that some of its features are inspired by an older system called Darcs. I gave Darcs a spin too. Darcs doesn’t have Jujutsu’s pleasant UX but it’s interesting for another reason. Where Git and Jujutsu both model the history of your repository as a tree of point-in-time snapshots (i.e. commits), Darcs instead models it as a tree of patches.

If you’re a long-time Git user and aren’t that familiar with Darcs, it’s not

obvious how these models are different. Even though what Git does under the

hood is store snapshots, Git shows you patches all the time—when you run git diff, when you encounter merge conflicts, when you stage hunks into your

index.

So are these two models equivalent? Some people believe that whether you store snapshots or patches has implications for performance but doesn’t otherwise affect what is possible within your version control system:

If you have a repository with many objects (e.g. thousands or millions of code files,) then a purely snapshot-based versioning system would end up with repositories ballooning in size, as each version of each file has to be stored separately whenever there are changes.

If you have a repository where each file has many revisions (e.g. you have thousands, or say millions of commits), then a purely changeset-based versioning system would struggle with processing speed, as building a commit would require trawling through millions of commits to piece together a complete file.

I get the impression that most VCSes will have some mechanisms in place to mitigate around both of these problems - like Git which isn’t purely snapshot based and “kind of” uses changesets under the hood. But from what I understand, the basic trade-off between these two forms of storage in version control systems is between performance and space.

A common corollary to this line of thinking is the belief that Git became more popular than Darcs in part because it chose the right trade-off and is fast whereas Darcs is slow. Which reinforces the idea that the performance characteristics of each model are the most important thing.

Now that I’ve tried Darcs, I think the difference between snapshots and patches goes deeper than performance. But I’m having a hard time articulating exactly why, hence this attempt to work it out in writing.

As best as I can tell, the fundamental difference between the two models comes down to what a “base” is in each system.

What Is a “Base,” Anyway?

In Git, the idea of a “base” is implicit in the git rebase command, but

weirdly I’ve never read an explanation of what exactly a “base” is supposed to

be. There is no entry for “base” when you run man gitglossary.

If we zoom out a bit, every version control system has to have some notion of a “base.” Version control systems capture changes to the files in our repository over time; each change is defined by 1) the actual change itself, let’s call it the transformation, and 2) the state of our repository prior to the change. This second thing is the “base.”

You might wonder why we need to worry about the base as well as the

transformation. This is because some transformations could produce different

results or even become meaningless depending on the state of the repository

prior to the change. To take one example, the transformation “add foo to line

6 of bar.txt” works if bar.txt exists but doesn’t make much sense if

bar.txt does not exist. Our version control system shouldn’t let us get to a

place where we’re trying to add lines to a nonexistent file. So the base

provides necessary context for the transformation.

We can imagine some transformations that don’t need context. “Create bar.txt”

is one. If we think of this transformation as meaning “ensure bar.txt

exists”, then it doesn’t matter what files are in our repository beforehand or

what those files contain—if the file doesn’t exist we can create it and if it

does exist we can leave it alone.

In general, though, we need to consider the base. Even in this last case,

things get more complicated if bar.txt was previously deleted; what we’re

really doing now by creating bar.txt is creating a second version of

bar.txt. This might be important context for certain operations in our system.

Bases in Git and Darcs

In Git, every commit (excluding the root commit) has at least one parent

commit. A parent commit serves as the base for a change. When you run git rebase, or git cherry-pick (which is just a rebase of a single commit), you

are swapping out the parent commit and thus swapping out the base of the change

introduced in that commit.

The thing to understand about Git is that the base for every change is the state of the entire repository immediately preceding that change. This is a direct consequence of not storing the transformation but instead computing it, on the fly, as the difference between two subsequent snapshots. The base for each change has to be the preceding snapshot, which captures the state of all our files.

We said before that if we make the change “add foo to line 6 of bar.txt”

then we need context about the state of bar.txt. What we don’t need is

context about other files. In Git, though, even if bar.txt was last modified

several dozen commits ago, the immediately preceding commit is the base we get.

It doesn’t matter if the immediately preceding commit changed something

unrelated, like, say, bim.txt.

In Darcs, the notion of a “base” is more subtle. In Darcs, you don’t make commits; instead, you record patches. A patch captures the transformation part of our change directly and doesn’t require a reference to an immediately preceding snapshot. A patch can almost be thought of as just the transformation part of a change. The base comes in only when we need that extra context, such as when we need a file to exist before we add lines to it; in this case we say that the patch depends on the previous patch that created the file. This previous patch is the base for our change.

The difference between Git and Darcs here is that the patch we depend on could be one we created a long time ago. It doesn’t have to be the most recent patch in our patch history. A patch can even depend on multiple previous patches, but that doesn’t make it a “merge” patch, just a patch with a base composed of multiple other patches.

In Darcs, our patch history is always shown as linear. However, the patches are

only partially ordered in reality. We can get a better sense for this partial

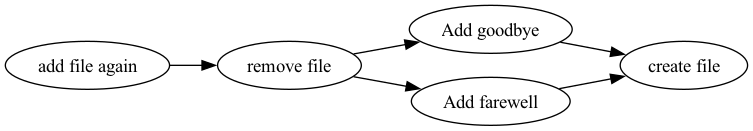

ordering by viewing the patch dependency tree using darcs show dependencies:

A dependency tree in a “hello world” Darcs repository.

This tree shows how our patches relate to each other, not chronologically but in terms of which transformations have to precede others. In Git, the notion of a “base” isn’t granular enough to capture any of this.

Affordances

This difference in what a “base” is in both systems leads to different affordances. Some operations are easier using Git and others are easier using Darcs.

I’ve realized that when I’m using a version control system, whether that’s Git or Darcs, sometimes I want to think in terms of snapshots and other times I want to think in terms of patches. By this I mean sometimes I want to think about specific states that my repository was in at a certain time, and other times I want to think about a transformation I want to apply without considering a specific preceding state.

In Git, thinking in snapshots is easy. If I want to revert my working directory

to the state it was in at the v1.2 release, I can just checkout that snapshot.

If I want to switch to several different states my repository was previously in

to search for when a regression was introduced, I can run git bisect and do

that. I can run git log to get the full picture of all the states my

repository has been in and how they relate to each other.

In Darcs, I can do some of these things but it isn’t as natural. When I want to

revert my working directory to a previous state, I have to “unwind” several

patches to get there. This should produce the same result, but doesn’t map as

well to my mental model of just moving to a fixed, previous state. Darcs has an

equivalent to git bisect called darcs test --bisect, which can help me find

a version of the repository before the bug was introduced but not the

version that was literally what whoever wrote the bug was working with when

they made their erroneous commit. The ordering of patches in the output from

darcs log reflects the order in which the patches were applied locally and

might not be the same for other people; it’s hard to get a sense for the actual

historical development of the codebase over time.

But when I want to think in patches, Git is the system that makes it hard. Something that is a huge pain to do in Git is keep a change you want to have locally and apply it on top of whatever you pull from a remote. Your local change might be a change to a configuration file that hardly ever gets updated; even so, you have to rebase your change on top of unrelated changes every time you pull from the remote. Similarly, when composing a PR, it’s natural to think of each of your commits as a patch you are introducing on top of the main branch. If you want to keep related changes in a single commit, or order the commits so that code that depends on other code gets introduced later in the commit sequence, you find yourself doing a lot of tedious interactive rebasing as you develop the feature.

In Darcs, all these things are natural because Darcs allows you to think of

patches as transformations most of the time. The bases have to change less

often so they can be more invisible. Making a local patch and then

pulling unrelated patches from a remote is trivial. Composing a series of

patches that implement a single feature would also be easier and wouldn’t

require constant rebasing. You would have darcs show dependencies to help you

understand the relationship between your patches. A reviewer could look at your

feature as a tree of changes rather than a sequence of commits, which might

help them better grok your work.

So, yes, while the choice between snapshots and patches has major performance implications, it also determines what is easy and what is hard for users to do within your version control system. It’s probably true that Git became more popular than Darcs because it was faster, among other reasons. But if we’re trying to learn lessons that we could apply to the design of future version control systems, what this choice of models means for the affordances of your system might be the more important lesson.